What could make me get on the metro in Helsinki for the first time? A visit to the Marimekko factory in Herttoniemi, a place I’d never been to in this growing city of more than one million.

Into the Metro (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

But here’s why I headed off into the unknown: I was on a journey into the past. That’s because my first real job was as a sales clerk at a Marimekko store. I wanted to improve my Finnish, but I was successful mainly because I spoke English — and I was able to sell huge amounts of merchandise to tourists.

Even then, Marimekko was known outside Finland, particularly in the United States, where its former first lady, Jacqueline Kennedy, had worn several Marimekko dresses during her husband’s presidential campaign.

Known for their bright colours, Marimekko designs mainly feature abstract natural designs, all printed in durable cotton.

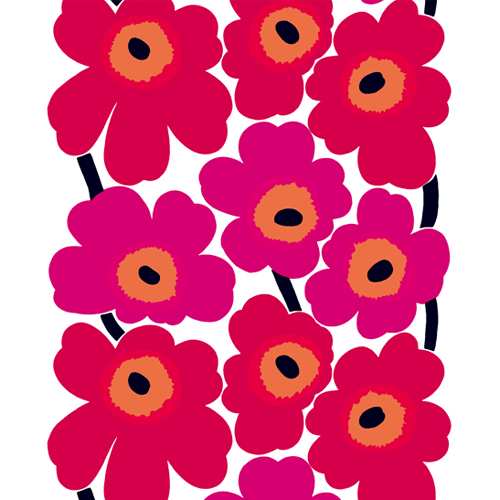

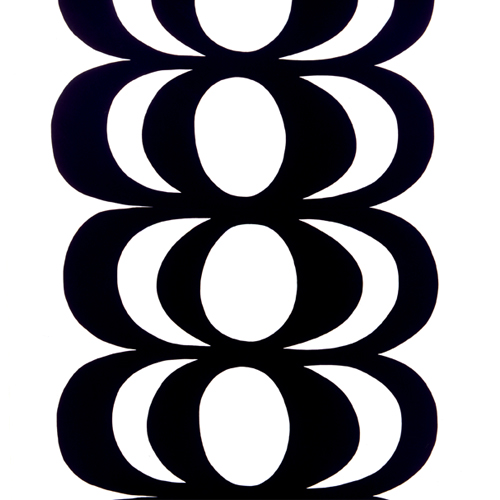

Among my favourite designs:

Unikko

Kaivo

and Tuuli.

and Tuuli.

Marimekko was all that many people could associate with Finland, that is, besides sauna — a bit like how Inuit carvings and prints once defined Canada’s Arctic.

Marimekko started out in 1951 as a family business, owned by Armi Ratia. And when I worked for the company, Ratia still brought staff to her seaside villa outside Helsinki for parties that were memorable for their food — and drink (I’d like to say I recall more of these events, but I can’t.)

We, the sales staff, young students like me, along with some professionals, worked 12-hour shifts for about $1.25 an hour. I received a free Marimekko outfit as well as discounts on clothing and material (I still have lots of dresses and metres of fabric from the three summers I spent working at Marimekko stores.)

Marimekko is the same now, but changed: It’s a global, publicly-traded company. And, like Finland, which was used to be homogenous and isolated by its Arctic location and language (related to Inuktitut), it’s more international.

Finland used to have few residents, apart from its Roma (Gypsy) population, who weren’t Finns, Swedes or Saami. You could go a day or a week without seeing a person of colour. You couldn’t find a pizza or even any fast food at all, but now, at least in Helsinki, you can choose from many ethnic restaurants and there’s a new multicultural look to the city.

Marimekko fabric on sale at the factory store in Herttoniemi. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

So how do you bring Marimekko into that new global reality, to become the Ikea of Scandinavian clothing and accessories? Today Marimekko isn’t just striped T-shirts and bright fabric: Its line includes everything from paper napkins, cups, towels and bedding to t-shirts and high-end dresses — and even café dining.

A display at the Marimekko factory store in Herttoniemi. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

Marimekko has outlets in 40 countries, with 154 shops in North America, Europe, Asia and the Pacific region, opening new stores in Singapore, Bangkok and Dubai in 2015. And this spring Marimekko launched a lower-priced design line with the big U.S. chain, Target.

But “Target’s Marimekko Collection Draws Muted Response,” said the Wall Street Journal, noting such collaborations are supposed to help the retailer create a buzz — but it seemed that during the Target promotion that Europeans were mainly lining up to buy the Marimekko collection.

Marimekko’s 2015 annual report shows that keeping ahead of the slagging global economy has been hard. But the Marimekko brand (now a borrowed word, “brändi,” in Finnish) can show its strength in global market, CEO Tiina Alahunta-Kasko said.

That brändi is now worth 186 million euros and the company had sales of 96 million euros. So there’s a lot of stake for Marimekko.

I toured the Marimekko factory in Herttoniemi with Sanna-Kaisa Nikko, the company’s PR manager for Europe, North America and Australia.

The newly printed fabric is rolled into huge rolls at the Marimekko factory (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

In the factory, quiet on that morning, Nikko said Marimekko is now all about making the old new, “cherishing what we have,” and getting it more out to the public. And this means coming up with new products, like towels with raised designs, and using updated materials, not just cotton, she said.

It also means Marimekko is taking old patterns and redoing them, maintaining the “timelessness” of the product, Nikko said.

Marimekko fabric rolled up into round bolts which will then be cut into 15-metre bolts. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

Today, Marimekko design and fabrics may have their roots in Finland, but they’re not all made in Finland.

“It isn’t realistic to make everything in Finland” Nikko said, because it’s a country with high wages and production costs.

But she said company looks for the best quality and ways to keep it… well… Finnish.

And so it is, that in nearly every home in Finland, you’ll still find something from Marimekko — although some of my friends complain that the clothes are made to appeal to smaller Asian customers than to sturdy Finns.

That Asian market looks to be booming: On my way to the factory from the Metro, I couldn’t get lost because I saw many Japanese tourists carrying heavy Marimekko bags, so I knew I was heading in the right direction.

When I went downtown to the Helsinki store, I discovered that the downtown store where I worked now has a Japanese salesclerk who does what I did so many years ago — that is, sell.

A Japanese salesclerk helps a Japanese customer in her own language at a Marimekko store in downtown Helsinki. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)