When you get to travel somewhere you have wanted to, that’s a great feeling.

I loved driving down the fiords in Norway.

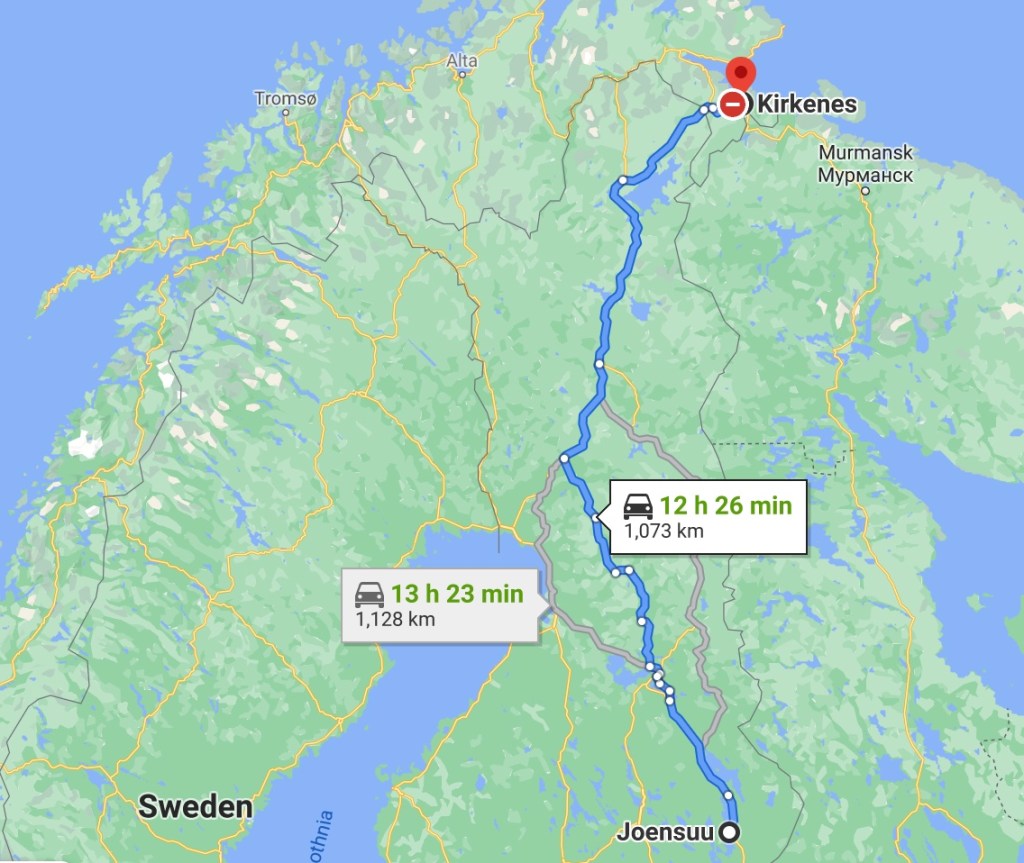

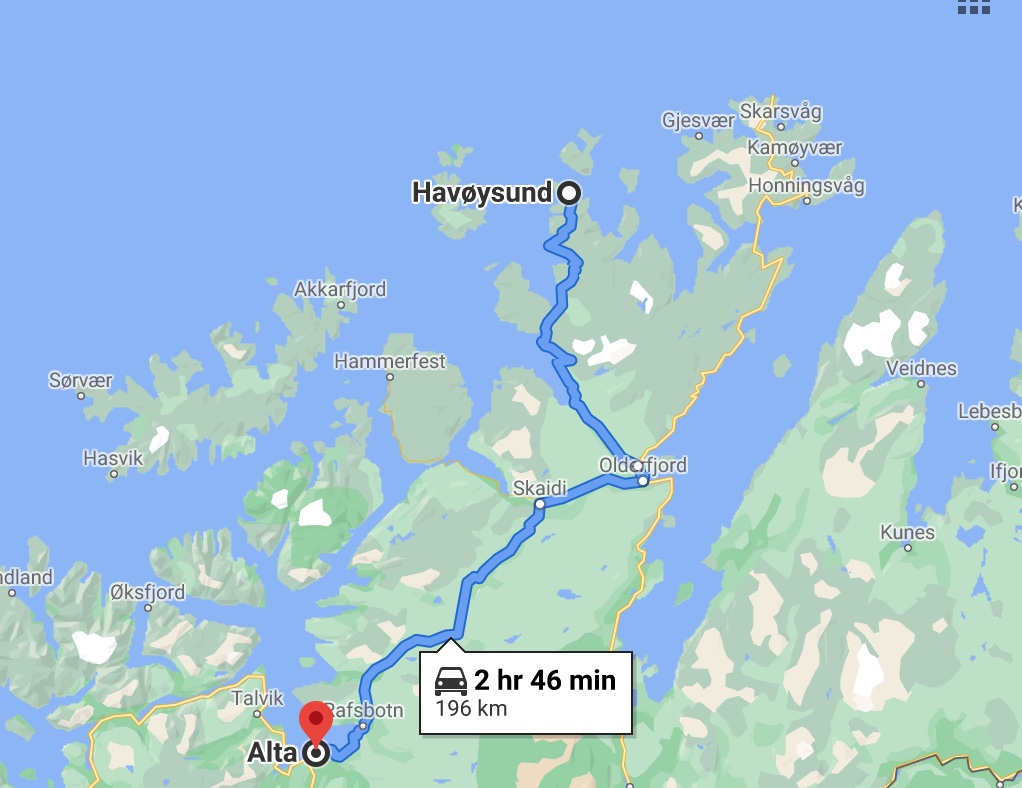

It took a while before I could find some sun. First, I had to buy some boots. I stopped in Alta where I found a pair of blue rubber boots with a reflective stripe: I would keep these on for most of the next week.

In Alta, I wanted to see the rock art. I had visited Qajartalik, off the coast of Nunavik, with its mysterious mask carvings.

But Alta was different: it was a World Heritage Site, a designation that brings money and protection.

Anyone could pick up a piece of ancient mummified wood in Nunavut’s High Arctic, or write graffiti over Nunavik’s delicate rock carvings.

Protecting fragile Arctic prehistory is not an easy task. But when a site has the status of a World Heritage Site, the job is much easier.

Money, attention and protection: these were among the benefits of being a World Heritage site, which were obvious in Alta.

There, several thousand rock carvings, some of them more than 6,000 years old, have been on the World Heritage list since 1985.

This listing opened doors to new money and global publicity. After that thousands of people from all over the world came to Alta to see the rock carvings and visit the interpretation centre. At the same time, there were strict laws protect the rock carvings.

The carvings in rock, of people, boats, animals and fish, show some of the beliefs and rituals of the ancestors of today’s Saami people, the original inhabitants of this part of the Arctic.

The rock carvings are thought to be a link between the people and spirit world, and the tranquil shore zone where the early Saami carved these drawings, the place the world of spirits and people met.

An international agreement governing World Heritage Sites preserves and protects these places to highlight mankind’s cultural and natural heritage.

But neither Nunavut nor Nunavik have any sites on the World Heritage list: in 2020, there are 1121 of them around the world.

Top candidates for World Heritage sites status in Canada’s Arctic continue the ancient rock carvings near Kangiqsujuaq, and the fossil forest on Axel Heiberg Island, not protected yet as a territorial part.

The rock carvings at Alta are painted orange-red, because more recent rock art in Norway was painted that way.

But Hebba Helberg from the University of Tromsø told me there’s no proof that this is the way they were originally painted.

“When you paint them, you’re interpreting them in a way,” he said when I ran into him in Alta.

The curators of the Alta site still let people experience the carvings as they were in nature, as a way of encouraging visitors to return as often as necessary to see the carvings.

During that summer of 2006, Helberg was supervising students who removed lichens from the rocks and uncovered even more carvings.

That kind of constant research is what the status of a World Heritage Site listing could provide — something Canada’s two vulnerable Arctic sites do not yet enjoy.

So you have missed Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3? Catch up…to be continued…