Like an iceberg, 1993: “Learning the language of the snows”

In May 1993 I was in Iqaluit, the largest community on Baffin Island, a place that I couldn’t find on a map two years before on my first trip north in Canada.

I was already on my second visit to Iqaluit, the first, only two months earlier, to work on a radio documentary on the creation of Nunavut, still six years away. And I was still throwing together radio and print freelance contracts to cover the cost of my travel and try to earn a living.

Work on radio documentaries for CBC’s national network, Radio-Canada, the Globe and Mail and other media allowed me to attend a three-week intensive Inuktitut program at Nunavut Arctic College.

There, I hung out in the hallways between classes, with that dazed feeling I hadn’t felt since high school. By 9 p.m., when the last class ended, with my brain full of Inuktitut, I could barely see straight. But then it was time to hit the books.

The group of 18 students was a teacher’s dream: We were patient and we listened attentively. That’s because we all wanted to learn Inuktitut.

I’d already studied Inuktitut for a year with help from anthropologist and Inuktitut-speaker Louis-Jacques Dorais at Université Laval. Most of my fellow students at Arctic College also had a basic knowledge of the language.

“You’re crazy to waste your time learning Inuktitut,” more than one person told me. “Isn’t it enough to speak English and French in Canada?”

But they’d obviously never visited a small Arctic community where all of the social life is conducted in Inuktitut. All of us in this class had been hampered by not knowing what’s going on or being able to join in.

I believed then that Inuktitut would become the language of tomorrow’s Arctic, because the creation of Nunavut was just around the corner: In 1999, Nunavut was to be carved out of the Northwest Territories.

My classmates included a few teachers from remote areas of Baffin Island — they wanted to be able to speak with students and their parents, a research scientist who spent months in the North out on the ice floes,with Inuit companions he’d like very much to talk with and learn from, an Anglican minister who needed to read the psalm book printed in Inuktitut syllabics to his congregation, two business managers and a company executive who wanted to talk to employees in their own language and understand what was happening on the job.

I wanted to understand older Inuit who rarely speak English. I wanted to more creatively pass away my hours spent waiting for the weather to lift by practicing Inuktitut. I wanted to know what’s happening. I kept thinking about Peter Murdoch and the other non-Inuit I knew who speak Inuktitut — if they could do it, I could, too.

In this class we learned, according to our text book, that Inuktitut has a complicated grammar whose many conjugations rival those of Finnish, a language that I learned just by hearing it spoken every day.

However, as adults, mastering how to speak clearly in Inuktitut about where we’re coming from and where we’ve been took hours.

One of our instructors — we hd four every day, teaching in shifts — got us down on the floor. We each chose a conveyance — an airplane, a snowmobile, a truck, a boat, a canoe or a dog sled, which we had to navigate in Inuktitut across mountains, over rivers and to and from various places — places such as Pond Inlet, whose Inuktitut name means where the hunter Mittima lived.

We became children again in this exercise, wrestling with such phrases as “Going by Twin Otter, I was on my way to Pangnirtung,” the place with bull caribou.

Every day, we dreaded dictation. A typical day’s 15 words included nunanngunngaujunga, the innocuous, but impossible, “I am going to his land.”

But we had fun, too, writing a soap opera whose action took place on the floe edge. And, to learn how Inuktitut answers a negative question, we sang “Oh yes, we have no bananas” in Inuktitut — that was a favourite teaching tool of our teacher Mick Mallon, who first learned Inuktitut in Puvirnituq in the 1960s.

My fellow student Stuart Innis, a research scientist with the Department of Fisheries, who died in a helicopter crash near Resolute Bay, Nunavut in 2000, and Mick Mallon, longtime Inuktitut teacher, relax after a day in the intensive Inuktitut course held at Nunavut Arctic College in Iqaluit in 1993. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

At the same time, we learned that the grammar of sentences in Inuktitut wasn’t always the same, even within one paragraph: Some elements are left dangling, their context being the reality outside, which the speakers intuitively know, and make reference to.

Alexina Kublu, who would later become Nunavut’s official languages commissioner, speaks to students in the intensive Inuktitut class at Nunavut Arctic College in 1993. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

Another instructor, Alexina Kublu, who worked with Mallon on the textbook that serves as our guide, spent a lot of time trying to explain family relationships. She explained that each Inuk bears the name of a dead relative and actually becomes that dead person, inheriting his or her relationships as well.

“I would like my mother to live in Igloolik,” an Inuk uncle might say to a new mother, she said, giving her baby his late mother’s name. And, if your daughter has your great-aunt’s name, you might end up calling her “Mother,” especially if that aunt was like a mother to you.

The southerners, called Qallunaat in Inuktitut, imposed a new naming system. First, it was new names from missionaries, followed by government-issued numbers on “Eskimo” tags in the 1950s, and finally by new surnames in the 1970s.

Because family names were assigned almost at random, closely related families may bear completely different names today. That confused what was, to Inuit, an entirely understandable system.

“Do these relationships make it hard for a mother to discipline someone who is her grandfather?” asked a teacher-classmate, mulling over problems in his community.

I was thinking, if I ever understand this language, will I see the North more clearly?

Mary Wilman, who would later serve as the mayor of Iqaluit. teaches the Inuktitut names for the parts of the body during an intermediate class in Inuktitut at Nunavut Arctic College in 1999. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

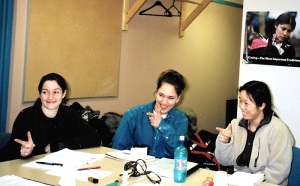

Jocelyn Barrett, Sylvia Cloutier and Siu-Ling Han participate in an exercise during the 1999 Intermediate Inuktitut class at Nunavut Arctic College in Iqaluit, which involves “shooting” the right person, according to the command in Inuktitut. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

A few years later, I took another course at Arctic College at an intermediate level, with a small group of students taught by Mary Wilman of Iqaluit and Mallon.

After this course, I could listen to the radio more easily, watch television, have a simple conversation, even take down Inuktitut telephone messages and put a trilingual message on my voice mail message.

My improved understanding of the Inuit language did save me one day, when at an airport in Nunavik, I heard the Air Inuit agent saying that there is only one more seat on the small airplane, but there were many people on the stand-by list — which included me. I dashed up to the counter and made the flight.

I upgraded my skills in Inuktitut enough to understand the flow of comments at meetings and to answer questions. Once I sat in the bar in Kuujjuaq, Nunavik’s largest community, where you hear more Inuktitut than in Iqaluit, and struck up a conversation with the woman sitting next to me in Inuktitut.

“But you don’t look like you speak Inuktitut,” she said.

My teachers at the intensive Inuktitut course held at Nunavut Arctic College in 1993: Alexina Kublu and Mick Mallon, who pioneered Inuktitut teaching in the eastern Arctic. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

The next instalment of “Like an Iceberg” goes live on April 9.

You can read the first blog entry from April 2 here.

You can find previous instalments here:

Like an iceberg, 1991…cont.

Like an iceberg, 1991…more

Like an iceberg, 1992, “Shots in the dark”

Like an iceberg, 1992, “Sad stories”