Like an iceberg, 1997, “Qaggiq” cont.

At midday, as the month of January progressed in Igloolik, the white landscape lit up with the sun, although the full moon was still visible far up in the sky. The Return of the Sun celebration was over and done. Finally, I could see where I was going.

Kept from leaving Igloolik by storm after storm, I had lots of time prepare other stories: I met Zacharias Kunuk, producer and director of the 13-part, 1995 series Nunavut: Our Land, whose 2001 Inuktitut-language feature film Atanardjuat would go on to win many awards.

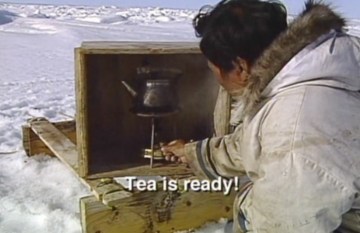

Nunavut shows long, beautiful shots of hunting and other activities around Igloolik as the series follows a group of Inuit around Igloolik in the mid-1940s through a year-long cycle.

In episode six (which you can now watch online on Isuma TV) the action takes place in the spring of 1946.

“It is the season of never-ending days. Two dog teams searching the spring ice, men and boys hunting day and night. Seals are everywhere: at the breathing holes, sleeping under the warm sun.”

Such images had helped draw me to Igloolik.

And, for me, the opening shots of Nunavut, with the dogs steaming ahead over the ice, always seemed to capture all the energy of moving towards the new territory’s creation in 1999.

When I met Kunuk in his Isuma Igloolik office building, he was not yet that well-known outside the North, where Nunavut had been broadcast on northern television networks.

We talked about how Kunuk first got started in film — by recording elders on a hand-held video cam.

“I didn’t think that when I videotaped something, five years [later], they’re dead and you still see their image talking. That’s when I got it — that it’s very important to record them now, because what they’re saying is going to become important years down the road,” Kunuk said.

His first real film production in 1988 was called Qaggiq, about a drum dance celebration in a big igloo.

Working with elders on Qaggiq, which required repeated takes, was not always easy.

“You have to do it again and again. There’s an old lady inside an igloo, and my job is to have her do it again. We don’t normally order our elders, but this time, we’re saying, ‘do it again,'” Kunuk said.

There was no script, no set dialogue. Everything was based on an “idea,” Kunuk told me.

“Back before we got this new way of living, pop and chocolate bars, our parents used to tell us legends and that was like being in the movies. It’s always here. You just have to visualize it,” he said.

And, dressed in traditional clothing, the actors, all locals, just picked up on that and improvised.

In the end, they forgot they were acting, Kunuk said, “because they’re really doing it. They’re preserving the culture. This is one way of preserving the culture.”

At one point during the production of Nunavut, Kunuk learned a polar bear had been killed on an island, after the polar bear had been attacking hunters camping there. Kunuk got all the actors into costume and went to the scene.

At one point during the production of Nunavut, Kunuk learned a polar bear had been killed on an island, after the polar bear had been attacking hunters camping there. Kunuk got all the actors into costume and went to the scene.

“It became the best Nunavut series. It was not play. It just happened. We made the best use of it.”

But the staging sometimes required for filming didn’t bother him because “everything we see on TV is staged.”

Kunuk, who started working full-time on his films in 1991, vowed in 1997 to make films that would be different — like his Inuktitut-language Nunavut series (now subtitled) — and which would have an “Inuk perspective.”

“To make them now is my career,” Kunuk said. “While our elders are still here, while the knowledge is here because it’s rapidly going.”

It’s all about Inuit self-respect, he said — “You have a goal. Our goal is to do it for real.”

Many films on the North and on Inuit offend him, Kunuk said. That’s because in films there’s usually a Qallunaaq (non-Inuk) who is the centre of the action. In Nunavut, a missionary (played by Kunuk’s longtime collaborator, Nunavut producer and director of photography Norm Cohn) took on a cameo role: that was all.

“I get offended. Every time there’s a movie, Inuit get the backstage,” Kunuk said.

To make Nunavut the most authentic as possible, that meant building a qammaq or sod hut: “an old woman directed her family to build this. She was directing others, do this, do that. She remembered how to build it.”

Before any production, there was a lot of research, talk with elders and consultation with a cultural advisor to make sure the sets would be accurate.

“We wanted something that would stay around for a long time,” Kunuk said. “We wanted to do it. They wanted to preserve.”

The message, about maintaining traditions, can be found right there in Nunavut‘s second episode: “Igloolik, Spring 1945. Many changes have taken place. On the hill above the tents, they now find a wooden church and a priest. Sharing the fresh caribou feast, telling stories, Inuit are interrupted by the bell ringing. Inside the church the sermon is clear: Paul 4:22, ‘Turn away from your old way of life.'”

Nunavut‘s filming itself was also challenging, requiring Kunuk and the crew to run around with the heavy cameras on komatik sleds alongside the dog teams and load all their gear into boats.

Batteries and tapes often froze during filming. Sometimes the viewfinder would stop working due to the cold, “so the camera still works, but you don’t know what you’re filming.” Boats broke down. And, during a walrus-hunting sequence for Nunavut, the camera almost fell into the water.

Kunuk’s Isuma Igloolik productions office was so cold that we then ended our conversation on that day in January 1997.

But later I thought what Kunuk wanted to do and what I wanted to do were not that different: He was set on preserving the past for the future, so Inuit would know what life was like, while I recorded the present so people would see how today fit in with what happened yesterday and what would take place tomorrow.

Read more from Like an iceberg’s “Qaggiq” May 8.

You can read earlier instalments here:

Like an iceberg: on being a journalist in the Arctic

Like an iceberg, 1991…cont.

Like an iceberg, 1991…more

Like an iceberg, 1992, “Shots in the dark”

Like an iceberg, 1992, “Sad stories”

Like an iceberg, 1993, “Learning the language of the snows”

Like an iceberg, 1993 cont., “Spring”

Like an iceberg, 1993 cont., “Chesterfield Inlet”

Like an iceberg, 1993 cont., more “Chesterfield Inlet”

Like an iceberg, 1994: “Seals and more”

Like an iceberg, 1994, cont., “No news is good news”

Like an iceberg, 1994 cont., more “No news is good news”

Like an iceberg, 1994 cont., “A place with four names”

Like an iceberg, 1995, “More sad stories”

Like an iceberg, 1995 cont., “No place like Nome”

Like an iceberg, 1995 cont., “Greenland”

Like an iceberg, 1995, cont. “Secrets”

Like an iceberg, 1996, “Hard Lessons”

Like an iceberg, 1996 cont., “Working together”

Like an iceberg, 1996 cont., “At the edge of the world”

Like an iceberg, 1996, more “At the edge of the world”

Like an iceberg, 1996, cont. “Choices”

Like an iceberg, 1997, “Qaggiq”

Like an iceberg, 1997, more “Qaggiq”