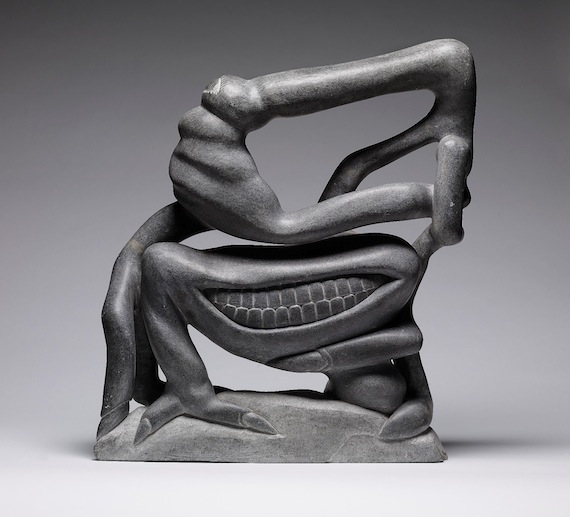

The Migration by Puvirnituq carver and printmaker Joe Talirunili. Talirunili’s carving depicts an event when the boat on which he was travelling was nearly trapped by crushing ice in Hudson Bay. (PHOTO/ART GALLERY OF ONTARIO)

1991: cont. from April 3

The night I met Peter Murdoch it was frigid and windy. I looked out of the window at J.’s apartment in Puvirnituq, and I could barely see the lights from the nearby houses. I’d arranged to meet Murdoch at the hotel, but I didn’t know where it was, so J. called the hospital van, which picked me up.

A view down a street in Puvirnituq, with the Inuulitsivik Health Centre to the right. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

I pushed the heavy metal doors, and headed tentatively down the narrow, carpeted hallway to what seemed to be the hotel’s communal kitchen.

“I’m looking for Peter Murdoch?” I said.

“You’ve found him,” said an older non-Inuit man, who resumed speaking Inuktitut to a younger Inuk.

“You speak Inuktitut!” I said.

“Even five-year-olds here speak it. So what’s so unusual about me?” Murdoch said.

We went into his small hotel room to talk, just a narrow bed, chest of drawers, a lamp, snow layered against the single window on the outside wall. Murdoch — a tall man, maybe in his 60s, balding hair and a nervous habit of clearing his throat that I ended up editing out of every taped interview. I knew nothing about Murdoch, so he told me about himself.

In 1991, he was the general manager of the Fédération des Co-opératives du Nouveau-Québec, then an association of 12 co-operatives in northern Quebec.

But he had started off as a Hudson’s Bay Co. employee back in the 1940s. Then, as a young man from Newfoundland, he was sent to Baffin Island to run trading posts. And, he learned Inuktitut and the Inuit way of life.

“I enjoyed hunting a lot, going out with people, seeing the way they lived,” Murdoch said. “Visiting in tents, learning the language. I never tried to learn it. If someone told me something, I just remembered it.”

Often he was the only white man in a settlement. In Pond Inlet, on the northern coast of Baffin Island, he’d spend the long days of spring and summer out on the land, sometimes walking for days. He found a people with values he admired.

“When I first came to the North I was lucky. I came early enough to see people living the old type of life,” Murdoch said. “Their ability to accept people as they were, their ability to share, to be completely non-judgmental, let everyone be what they wanted, their ability to live with time — if there was nothing to do, they did it gracefully, did it well and enjoyed it. When things were tough, no one complained. You accepted your life as it came and I felt then that we could have learned a lot from the Inuit and the ways they relate to each other.”

As he spoke, I was brought back to a North that seemed almost a perfect society.

“The only thing that made a person an outcast,” Murdoch said, “was if he was a danger to the rest of the people. Then, they would react to get rid of that person. You didn’t see problems until after people moved into communities in the ‘50s.”

Murdoch first came to Puvirnituq with the Hudson Bay Co. in the early 1950s, when people were still living on the land in camps, not far from the trading post. In Pond Inlet, thousands of seals could be found on the ice year-round, but in Puvirnituq, he found a much poorer environment.

The fledgling community then consisted of a trading post, a dwelling, a small shack and a couple of snow houses. That’s all there was. Two small camps were located within walking distance, one with eight or 10 snow houses, the other with four or five. People were hungry. There was a lot of sickness. At that time people would sell a small carving for tea, the next day for flour or lard to make bannock.

“Sort of a dead-end sort of life,” he told me.

Murdoch walked around the camps, bringing medicine, getting to know the people.

“Here you had a group of Inuit living for the next meal. Just what you can get for the next meal. Yet, in talking, they were articulate, intelligent. So, we tried to find a better way.”

That better way was to try and pool resources to invest in purchases that would improve the standard of living for everyone, like buying a new boat or more ammunition.

Part of all sales from carvings would be used collectively — and the camps would decide what do. An election was held, and the camps voted a leader. It was all self-motivated, Murdoch said. It was the beginning of the co-operative movement in northern Quebec.

“It was never,” he said with emphasis, “a community development project” — the kind of government-sponsored projects that are imposed from the South by people from the South.

The market for soapstone carvings was just beginning in the South when Murdoch visited those camps. And sales of carvings would be the base of the co-operatives that grew up at the same time that Inuit were moving off the land, into communities. Inuit in Puvirnituq were good carvers, he said.

“They idealized hunting because there was so little game. It came out in the art and Puvirnituq became quite quickly known for its realism, with a dream-like quality.”

Peter Murdoch in 1992, then the general manager of the Fédération des Co-opératives du Nouveau-Québec, stands by a shelf full of carvings from the Nunavik community of Kangirsuk on display at the showroom of the FCNQ headquarters in Baie d’Urfé, Quebec. (PHOTO BY JANE GEORGE)

I knew little about Inuit art the night I spoke with Murdoch, but I was wondering why the print shop closed. I had climbed through snowdrifts to reach this small building, now locked and boarded over.

Murdoch told me that it was because welfare pays more than art today. The recession in the South had cut art sales. Printing was an expensive operation, so it was the first casualty. Now, the co-operatives couldn’t afford to buy all the carvings that are produced, so people were giving up carving, too. There had been 60 carvers in Puvirnituq a few years earlier. When I met Murdoch, only about 10 men seriously carved.

“If this was happening to wheat farmers, there would be something done,” Murdoch said. “But there is nothing done for the Inuit, nothing. Here, we see a whole way of life, a whole group of people turning from being self-supporting to a welfare society. There is no economy except what they can do with their hands or tourism. Everything is tied to the southern economy, and it’s magnified in the North.”

The co-ops were suffering too in 1991, because, to keep consumer prices reasonable, they needed to have some other source of revenue as a subsidy, Murdoch said.

But the co-operative way of doing things, he said, was no longer being encouraged by government, as it was in the 1960’s, and Inuit themselves were becoming drawn to the new development corporations that feed on land-claim settlement money.

That night Murdoch brought me from an idyllic past where Inuit life was tough, but pure, almost a reflection of the stereotypical soapstone imagery, back to today’s difficult, modern reality. He was telling me that there was a battle being fought between big forces, different ways of thinking, of living, of doing business. Inuit may be the casualties, and no one’s doing or saying anything, he said. Inuit strengths are disappearing. Murdoch’s disillusionment struck through me, like a bolt.

“We can destroy them very easily as a people,” he said. “Or we could help them. We could see their value. We could develop that, help them. I don’t think that we are that concerned about their survival. If we don’t change that, there is no future for the Inuit, as a race, as a culture. They are finished.”

After two hours of listening to Murdoch, I ended the interview. I didn’t know much then about Inuit and the co-operative movement he worked for, but I was moved by his vision. On my way back from the hotel to J.’s, I almost got lost, stumbling through the snow, following the pale lights from the windows of houses and the howling dogs as guides.

I did my first short radio documentary for the Canadian Broadcasting Corp.’s national radio network on Peter Murdoch and the plight of Inuit carvers in the North.

But a producer in Toronto said “why should we care about this? A few Inuit that don’t have enough money for new snowmobiles?” and killed the piece.

The late Puvirnituq sculptor Eli Sallualu Qinuajua explored surrealism in many of his carvings, which include this carving called “Fantastic Figure.” (IMAGE/ AGO)

Like an iceberg continues April 5 with 1992, “Shots in the dark.”

You can read the first entry here.