Wouldn’t it be great if everyone in the circumpolar region could understand each other without translators or interpreters? At least one linguist thinks that may have been the case about 20,000 years ago.

Michael Fortescue, a linguist and expert in Eskimo–Aleut and Chukotko-Kamchatkan, believes that a group of people, all speaking a common language that he’s dubbed “Uralo-Siberian,” then lived by hunting, fishing and gathering in south-central Siberia (an area located roughly between the upper Yenisei river and Lake Baikal in today’s Russia, as shown in the map).

The area between the Yenisei River and Lake Baikal in central Siberia where early residents are thought to have spoken a common language called Uralo-Siberian that gave rise to Saami, Finnish and Inuit languages.

There, families whose migrations were ruled by the coming and going of glaciers during the Ice Age moved northward out of this area in successive waves until about 4,000 BC.

Some headed west along the northern coasts and others went east, eventually crossing the Bering Strait to North America.

They would end up living across the circumpolar region, with Inuit living from Alaska through to Canada and Greenland, Saami in Sápmi (northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and northern Russia) and Finns in Finland (or Suomi in Finnish.)

During those long-ago migrations, travelers took their common language, Uralo-Siberian, Fortescue suggests.

You can still hear today’s version of that language in Nunavut — where Uralo-Siberian developed into Inuktitut — and in Finland — where that language survived as Saami and as Finnish.

To me, someone who has lived in both regions and speaks Finnish (fairly fluently) and Inuktitut (not nearly as well) and can understand when people speak Saami (usually), the idea that there was once a united Uralo-Siberian family of languages makes sense.

That’s because the grammars of the three languages feel so similar (not to mention many shared cultural elements).

A family tree of the Uralo-Siberian and related languages which shows the various Inuit languages as well as Saami and Finnish and how they are related.

Indeed, on this family tree of Uralo-Siberian languages, Inuktitut and Finnish look like fairly close cousins.

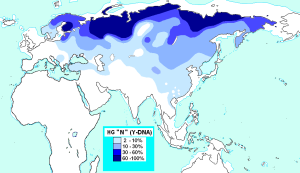

This map shows the spread of the genetic marker Haplogroup N “Y”, which goes from the northern coast of Scandinavia through Siberia towards North America.

This language family was first proposed in 1998 by Fortescue in his book Language Relations across Bering Strait . But some linguists still don’t embrace his proposal, because it looks at the spread of languages and people in a new way.

More recent genetic tests do show Saami and Finns share more genetic markers linked with Asian populations in the Bering Strait and beyond than do any other European populations.

As for this early language, Uralo-Siberian, Fortescue argues that some common grammatical marker features are recognizable in the Inuit languages, Saami and Finnish, namely:

*-t — plural

*-k — dual

*m — 1st person

*t — 2nd person

*ka —interrogative pronoun

*-n — genitive case

And you can still find verb roots in the Inuit languages of Canada and in Saami or Finnish as well as words in all three that appear to stem from that ancient common language:

Proto-Uralo-Siberianaj (aɣ) — ‘push forward’

Proto-Eskimo–Aleut ajaɣ —‘push, thrust at with pole’

In today’s Finnish — ajaa, ‘drive’

Or you can hear similarities in other words used today, such as:

• kina (who) in Inuktitut, ken in Finnish;

• mannik (egg) in Inukitut, monne in Saami, muna in Finnish; and,

• kamek (boot) in Inuktitut, gama in Saami, kenka in Finnish.

The spoken languages also sound similar because they’re spoken with a word-initial stress (that is with the first syllable being emphasized — i.e. Nu-navut, Su-omi.)

As well, words (both nouns and verbs) get their meaning from many added-on chunks that tell you, among other things, who did what and when and to whom. This allows for a precision that you don’t find in English.

For example, in Inuktitut and Finnish, even the notion of saying “there” must be precise — you need to say exactly where something is, whether it’s at a certain point nearby, here or there or further away.

For some experts, the enduring similarities in these languages, spoken by a majority of people who live within the jurisdictions of Nunavut, Greenland and Finland, reflect the amazing survival of that early Uralo-Siberian grammar and lexicon of words.

But its isolation in the North in may also have had something to do with the Uralo-Siberian language’s endurance.

The Origin and Genetic Background of the Sámi suggests that Saami and, to a lesser extent, Finns were able to maintain their separate language identities over the centuries due to their geographic isolation in the Arctic while other peoples were losing their languages to Indo-European speakers from the South.

We now see different situations between the Inuit languages, Saami and Finnish — the largest of the three languages, which is spoken by more than five million people in Finland.

In Like an iceberg. I talk about learning Inuktitut.

In a future post in A Date with Siku girl, I will talk about what it was like for me to learn Finnish as a young girl and what this experience reveals — at least to me — about language learning and preservation.

(For this post, I consulted so many sources online that I have not provided links to them all, but if you’re curious about the relationships between the ancient Uralo-Siberian languages, I urge you to do your own online searches and see what turns up. There appears to be many disputes over all the genetics and linguistics about which I could write a book, not simply a blog post. As for me, I’d be interested in receiving feedback from those more knowledgeable than I am in this area. Since publishing this blog in 2014, I received this very interesting list of words in Inuktitut, Finnish and Estonian:

An interesting read, Jane. I’d love to travel to Finland if only to test my own abilities to pick up on the similarities as you relate them here. As an Inuktitut speaker with an accumulated experience in translating and interpreting I’m still keen on learning more about the circumpolar language(s). If you ever need me to travel with you, just holler and I’ll come with you to Finland!

LikeLike

Ida,

Thanks for your comment.

I just got back from Finland, but I’ll keep your offer of a travel companion in mind for my next visit!

LikeLike

Pingback: Stepping back in time at Finland’s Marimekko | A date with Siku girl

Reblogged this on A date with Siku girl.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Polar Lights.

LikeLike

You are right they resemble. I have many times thought the same. Northern languages seem anciently related in a west/east direction.

In northern Saami

Gii (who)

Geen (whos)

Achi (father)

Monot (eggs)

Eadni (mother, world/soil)

Guolli (fish)

Uksa (door)

Goaskin (eagle)

Mielas (happy/positive)

Nisonna (women – also onna in Japanese btw)

Aibmi (cutting needle)

Niehku (dream)

Nágut (force)

And so on….

LikeLiked by 1 person

I very much enjoyed reading and learning from your blog post! I have been learning more about the Sámi recently, so found it quite informative.

LikeLike