1993, “Chesterfield Inlet,” continued:

“Right now, I can’t forgive,” a former student told me during an interview at the reunion of former students of Sir Joseph Bernier School, held July 1993 in Chesterfield Inlet.

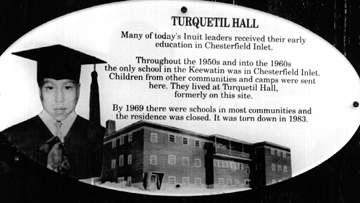

The reunion took place in the community’s recreation centre, erected on the site of Turquetil Hall, the student residence that had been torn down 10 years previously. During the day it was hot — with temperatures in the mid-20s. Mosquitoes, dull with the heat, flew around.

“Being six years old and sexually molested here, I know the feeling of being trapped. I hate what he did to me,” the man said.

Outside the centre, I was sitting and talking with this tall, good-looking man. As we spoke, it was as if he was reliving the bad memories of his school days here, when he arrived as an innocent six-year-old.

Soon after he arrived at the school he was sexually abused, he said in a quiet, slow voice.

“Dead, dead inside, that’s what I felt. Pain. Hurt. I don’t know if I had anger because I couldn’t distinguish between anger, hurt and pain at that time.

“When they did something to you that was so filthy, there’s no feeling, just hurt. Never mind the physical pain.”

I tried to focus on what he said and the buzzing of the mosquitoes as he spoke.

“We had no protection …I’m not going to go to heaven if I tell the secret … pray like hell. That’s what we were taught and God’s going to forgive the wrong things you did. Over 30 years later, the pain’s still here. Was it my sin? I don’t think so.”

During the reunion some of that pain surfaced. In the gymnasium, a terrible keening arose when they mourn the loss of a former student killed by her spouse, also a former student.

But there were other lighter moments. One night during the reunion there was a talent show. Residents of Chesterfield Inlet also turned out. A large flat drum was placed in the centre of the gym. Men and women took turns picking up the drum and singing traditional Inuit a-ya-ya songs. Some former students never learned how to dance well when they were at residential school. As they reclaimed those lost years, they got up, took the drum and sang.

The morning always came too early. At 3 a.m., the sun made our tents glow. Returning students didn’t seem to sleep at all. An early morning walk brought us in front of the place where they used to line up every day to sing “O Canada.”

The Catholic Mission Hospital of St. Therese in Chesterfield Inlet, which contained 30 beds, was once the largest building in the eastern Arctic. (PHOTO FROM WIKIPEDIA COMMONS)

Nearby was the former hospital, built 60 years ago, a three-story building with a flat roof. Old wagon wheels, painted white and red, beside the entrance, like reminders of a time, not so long ago, when this was the missionaries’ frontier. Above the door, a statue of the Virgin Mary. The former St. Therese Hospital was, for many years, the largest building in the eastern Arctic. I asked for a tour.

“It was built on a rock,” to last forever, said Sister Naja Isabelle, one of the Grey Nuns who then still took care of severely handicapped children in the former hospital. “And with only the annual sealift to bring in supplies, the hospital had to be entirely self-sufficient.”

Enormous reservoirs for fuel and water filled the basement. A generator supplied power. For years, the nuns kept the only chicken coop in the Arctic. And, even now, there was a greenhouse, with lush-looking lettuce and other vegetables.

“Last year, we had three meals from potatoes here,” Sister Isabelle said.

We toured the entire building, visiting the handicapped children. Their rooms were bright and cheerful, with posters depicting each child’s family, likes and dislikes posted above their beds. Paulusi, deaf and blind, was Sister Isabelle’s favourite. She picked him up and he giggled.

Sister Isabelle gave me a copy of a book on the life of their order’s founder, Ste. Marguérite d’Youville: I felt ready to take my vows.

I ate lunch at the mission with Bishop Reynald Rouleau. His diocese, the largest in Canada, covers two million square kilometres, 24 eastern Arctic communities. Bishop Rouleau, who chain-smoked as we talked, said he was depressed after revelations made during the reunion and the demands from residential school survivors for financial compensation from the church.

“The [Roman Catholic] Church seems like a powerful big thing,” Rouleau said. “I suppose the Church was that kind of institution. But I don’t have much power. I survive. Things have changed.”

Later that week, he did issue an apology, but it fell short of satisfying former students.

“During the last 35 years there have been many changes in the world and very rapid ones in the Canadian North. The school was only one agent of change and its role in all the changes that have taken place will be determined by history,” he said.

“I hope that this reunion has been a step in the right direction to help us all progress forward in order to respond to the social and spiritual challenges facing the people of Nunavut.”

Sister Vicky was also staying at the mission. She once taught at the federal school. I asked her how she felt during the reunion. She said she had been in a state of shock.

“All week, I knew everyone that went to speak. I knew them when they were eight, 10 or 15. I said how can it be? And I understand that if someone’s abused, that everything before or after it, it doesn’t count,” she said.

But Sister Vicky said she didn’t think it was right to hate the Catholic church for what was done.

“If your brother hits you, are you going to hit your mother and dad and brothers and sisters and uncle? You’ll hate them for the rest of your life? The church is not a building — it’s just people.”

Sister Vicky said she was furious at Brother Parent. He was well loved, she said, a storyteller who fooled them all. In going through mementos from her years at Chesterfield Inlet, she found his photo and tore it into pieces.

“I throw it in the garbage. I say, ‘good for you.’ That’s hate. ‘What you did is terrible.’ He never hurt me, but he hurt people I love, small children, so this is how I feel.”

Not far from the village, small groupings of stones went unnoticed during the reunion. These were remains of the ancient Thule people, who once lived here. Beside the foundations of their vanished homes, there were rectangular depressions where sod was cut for walls.

Former students searched for the outlines of Turquetil Hall, still visible around the edge of the recreational complex. The old foundation was almost as hard to see as those at the Thule site, but for them, the marks were clear.

Missed the first part of “Chesterfield Inlet”? Read it here.

“Like an iceberg” returns April 14.

You can read the first blog entry of “Like an Iceberg” from April 2 here.

Other previous instalments are here:

Like an iceberg: on being a journalist in the Arctic

Like an iceberg, 1991…cont.

Like an iceberg, 1991…more

Like an iceberg, 1992, “Shots in the dark”

Like an iceberg, 1992, “Sad stories”

Like an iceberg, 1993, “Learning the language of the snows”

Like an iceberg, 1993 cont., “Spring”

Like an iceberg, 1993 cont., “Chesterfield Inlet”

Here’s a detail from the stained glass window commemorating the legacy of Indian Residential Schools. This stained glass window, designed by Métis artist Christi Belcourt, is permanently installed in Centre Block on Parliament Hill. “In 2008, on behalf all Canadians, Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered a formal Apology to former students of Indian Residential Schools, their families and communities that acknowledged the impacts of those schools,” AANDC’s former minister John Duncan said in November 2012. “Today we continue on the path of reconciliation as we dedicate this new stained glass window. The window is a visible reminder of the legacy of Indian Residential Schools; it is also a window to a future founded on reconciliation and respect.” (PHOTO COURTESY OF AANDC)

Excellent reading Jane.

LikeLike